Jessica Schnebel, September 2004 Glamour Incomplete

Jessica Schnebel, September 2004 Glamour Incomplete |

SemiConductors:

Painting the Transmission of Information

Craig

Drennen, curator

Pharmaka Gallery, 101 West 5th Street, Los Angeles, CA 90013, May 6 through June 26, 2005

Avantika Bawa, New Delhi/Savannah, GA, Brett Callero, Green Bay, WI Lauren Clay, Atlanta, GA Craig Drennen, Savannah, GA Fred Jesser, Savannah, GA Heath Ritch, Los Angeles, CA Jessica Schnebel, Oklahoma City, OK Michael Scoggins, Savannah, GA Eric Standley, Backsburg, VA, Alexis Terry, Savannah, GA

Press

Release

Semiconductors

presents the work of ten young artists who use paint to realize their respective

conceptual goals. The works range from Eric Standley's traditional oil

paintings carefully cut and sews into shoes, to Michael Scoggins' oversized

superhero drawings, to Alexis Terry's metal can constellations of pigmented

plaster. Cultural references may be as muted as Heath Ritch's "stamped"

abstractions and Brett Calero's mediated "re-make" paintings, or as

obvious as Jessica Schnebel's one-month paintings of Glamour magazine covers

or artist/curator Craig Drennen's "Supergirl" series.

The artists in Semiconductors submerge themselves into the practice of painting without accepting the binary absolutes of previous generations. At a time when the act of painting suggests to some a retrograde attachment to materials over ideas, and the recurring "returns" to painting tend to valorize only the most the most predictable tendencies, these artists represent a new type of relevancy.

Their work becomes a site, like the surface of a silicone chip, where both information and materiality are managed. The end result is both painting as a material object that emits information, and painting as a flow of information governed by materials.

For additional information contact Pharmaka Gallery (info@pharmaka-art.org or call 323.954.8499) or Craig Drennen at adrennen@scad.edu.

Introduction

If syncretism means the integration of disparate or oppositional ideologies, then an exhibition of paintings in downtown Los Angeles by a group of young artists who met in Georgia would seem to qualify. I hold that painting is by its very nature syncretic, with one foot in the 15th century and the other in the 21st. In early May, 2005 I curated "Semiconductor : Painting the Transmission of Information" at Pharmaka Gallery (www.pharmaka-art.org/) in LA's historic, though now neglected, "bank district".

I proposed the exhibition around the premise of a semiconductor, the physical reality of a flat surface where information is managed, and my preferred analogy for contemporary painting. I limited the scope to artists who used paint to "conduct" portions of painting's history alongside the current cultural moment. Few of the pieces in "Semiconductors" reveal themselves completely at first glance. Even a seasoned viewer like Matt Gleason, who gave a packed house lecture at the gallery, seemed partially oblivious to the work that surrounded him (homepage.mac.com/rger/BadArt/iMovieTheater43.html).

I had been introduced to all of the "Semiconductor" artists in Georgia. The coastal Georgia town of Savannah has morphed into an unlikely crossroads for contemporary painting, thanks in no small amount to the faculty and students of the large art college where I also teach. Pharmaka started in LA as a group of painters, led in part by Shane Guffogg, whose ambitions generated the formation of a non-profit gallery space, right at the moment when city officials sought to revitalize that particular stretch of downtown.

During the days before the opening, some street activity from the neighborhood

spilled into the gallery space, reminding me of the "porosity" of

which Walter Benjamin spoke. A homeless man named Ricky stopped by every

day to do odd jobs and occasional security details. Yet as permeable

as the neighborhood seemed to be for Ricky, there were clear demarcations.

Pharmaka Gallery is on the northwest corner of 5th and Main. On the southeast

corner was a thriving drug trade that was suffered twice-daily drug busts.

That corner was ruled by some citizens claiming affiliation with one of LA's

more notorious gangs. I discovered this when they sent a messenger-a

homeless woman whose name I never learned-over to the gallery to protest an

artwork I had installed in the Main Street window. The work in question

was What I Did Last Summer by Michael Scoggins (www.saltworksgallery.com/artists/artist_index.html).

The piece was from a series by Scoggins using faux naïf drawings

and text on oversized simulations of notebook paper. The text is in the

voice of a child questioning the social views elder family members, but it became

clear that street-level LA drug dealers have no sense of irony. The woman

delivering the message made it known that the artwork in the window would result

in the gallery being destroyed by nightfall. I moved the work into a

backroom, in what was one of the more intense de-installations I've experienced.

Ricky did much to diffuse the volatility of the situation, which moved

from death threats to promises of destroyed property, before degenerating into

what seemed like 300 utterances of the word "motherfucker."

Avantika

Bawa, Untitled; Brett Callero, Don't Call It a Comeback

As the opening reception for "Semiconductors" started, I began to sense the palimpsest of that moment. We were in a gallery in a forgotten neighborhood in downtown Los Angeles, where investor money had already begun to silently flow. Organized criminals used the street to supply illegal narcotics to a public apparently hungry to have them. Simultaneously, a grass roots collection of California painters pooled their energies to open a gallery whose name stems from a Greek word meaning both medicine and poison. And on display was an exhibition of smart painting from artists who had briefly found themselves caught in the gravitational pull of Georgia. What follows is the "Semiconductors" curatorial statement, list of works, Users Guide, and images from the exhibition.

Curatorial

Statement

By 1874 it was found that electricity could carry both power and information. In 1906 an American inventor made a vacuum tube triode that allowed for the amplification of audio signals. In 1947 Bell Labs invented the first working transistor, a compact device that administered the transmission and resistance of electrical energy. By 1958 Texas Instruments demonstrated the first working integrated circuit that predicated the technological world we know today. In 1959 "planar technology" was introduced at Fairchild Semiconductor, wherein multiple circuit pathways were evaporated onto thin wafers of silicon-the most easily obtainable and frequently used semiconductor.

This history is convenient because the history of circuitry is concurrent with the reductive history of Modernism. The leap from vacuum tube to portable transistor mimics the move from painting's traditional pictorial space to the abstracted pictorial space after Cubism. The subsequent move from transistor to integrated circuit runs parallel to the radical flattening of the picture plane after Barnett Newman. As the scale of electronics hardware became exponentially smaller, its capacity to store information increased. In other words, the amount of manageable information increased as the physical material decreased. Early appliances required electrical power to operate sequences of components, but as the integrated circuits became smaller and smaller the components became redefined as a means to reroute and decode the flow of electrical information. The rush to privilege information, coupled with the manic drive toward immateriality could just as easily describe the first generations of conceptual artists. As late '60's conceptual art became "dematerialized" it came to increasingly depend upon memory storage and retrieval. (wall works by Lewitt and Weiner can be infinitely reborn as long as the initial instructional code exists). And if the cultural energy directed toward advancing complex circuitry reads as a sublimated desire to recreate the processes of the human mind, then to value information over material legitimizes "mind over matter."

Painting found itself in an awkward position, caught in a seeming aporia. Participation in the practice of painting suggested a retrograde attachment to materials over ideas, and a complicity in the worst aspects of bourgeois commodity culture. Artists striving for relevancy within the art world were expected to apostatize painting in favor of nomadic relationships with varied processes. The recurring "returns" of painting tend to valorize only the most predictable tendencies, whether the manic machismo of the Transvangarde to the pompier figuration of Currin or Yuskavage. With notable exceptions (Levine, Komar & Melamid, Polke, et al) painting has never been treated as a viable site for critical practice.

Semiconductors is meant to acknowledge a young generation of artists who choose to occupy a more nuanced position. These artists are all-some broadly, some narrowly--painters. Their work becomes a site, like the surface of a silicone chip, where both information and materiality are managed. They've chosen to navigate contemporary art within a vehicle that is both static and active, both very old and always new. Some painters in Semiconductors use sophisticated forms of mechanical reproduction, while a few use anachronistic versions, and others none at all. Painting's commodity status, which seemed so problematic two decades ago, is handled deftly by these painters who each incorporate their own hand into the process. They submerge themselves into the tradition of painting without accepting the binary absolutes of previous generations. The painting becomes a permeable membrane with its own history on one side and contemporary culture on the other. Like a capacitor controlling electrons, these painters modulate just how much information is transmitted through their work from both directions. The Semiconductors artists allow part of painting's tradition to flow through. They also allow aspects of their own lives and the greater culture to flow through as well. The end result is both painting as a material object that emits information, and painting as a flow of information governed by materials.

ABOUT THE ARTISTS

Avantika Bawa makes aggregates of painting, installation, and sculpture that are simultaneously humble and ambitious. Bawa begins with blue latex paint, which serves as a convenient analogy to water. She incorporates simple objects, such as corrugated cardboard or Styrofoam, into her works that become key visual components. The lightness of these objects combines with the solidity of the architecture to form an absurd theater of scale and balance. Her invocation of the readymade tradition allows the utilitarian origin of the objects to leak through, but not without becoming transformed to fit Bawa's propensity for altering sites with unlikely combinations of color, line and shape. (...) was first realized in the Bawa's studio in 2003, and has been adjusted as a response to the Pharmaka site.

Brett Callero creates works he calls "remakes." Callero begins these remakes by creating a freely associative installation in his studio with images and text fragments pulled from the culture around him. Visual and linguistic non-sequitors are combined and re-combined onto paper, post-its, or even the wall to create a total collage environment. He then photographs the walls of his studio and downloads the images for a second level of manipulation. Callero eventually selects image/text combinations to be printed onto canvas using a photomechanical process as is evident in The Eagle Has Landed and Don't Call It a Comeback. The printed canvas is stretched onto modular stretchers and exhibited as "remakes." The last step of the process is to stretch a canvas, but the first step remains the creative practice of the studio and the activity of the artist's hand.

Lauren Clay primarily makes large works on paper. The titles of her pieces usually indicate that each piece is a "proposal" for a subsequent work that may never actually exist, as in Proposed Communal Hideaway Unit for Virgins. Clay manages to create pieces that are physically large without seeming monolithic. The geometric images Clay puts into these works are complemented by rhyming three-dimensional forms that actually hold the paper to the wall. The rounded corners of the paper and the soft edges to the forms give the impression, at this scale, of miniatures made inordinately large. The pieces invite investigation, while simultaneously deferring attention to the "final" work that they propose.

Craig Drennen has been making nearly identical paired works since 2000. In 2002 he turned his attention to the1984 movie Supergirl. His work-more conceptual than Pop-still privileges the handmade mark. For new each pair, Drennen makes dozens of drawings on inexpensive notebook paper. He then selects the most casually executed drawing that he then carefully recreates. In Helen Slater As Supergirl Front Near & Far and Helen Slater As Supergirl Back Near & Far, Drennen portrays two versions of the front of one of his notebook drawings, as well as two versions of the corresponding back. Drennen might not have the resources to produce a film, but he can re-code an existing film according to his own investigation.

Fred Jesser begins his work by attaching printed materials over traditional formats. He then devotes himself to studying the pattern and locating ways within which he can insinuate his own presence, as in Horseplay. For Jesser it is almost as if he begins each piece by placing himself into a readymade structure, that he then methodically subverts. The more he paints onto maps or printed fabric, the more vocal his refusal to reject what the material asserts. He begins by allowing the full transmission of the fabric's information, and then scrambles that transmission with the addition of his own hand. In many instances, Jesser's intervention into a pictorial system will reduce it to a background presence, as in Fabulous: Part II.

Heath Ritch makes what at first glance seem to be competent abstractions, but. the truth is more complex. Ritch begins each piece by carefully painting an image from the pages of a current art magazine. While the paint is still wet, he begins pressing a separate piece of unprimed canvas onto the surface. He repeats the "stamping" process until it obliterates the original image. At the end of the process Ritch exhibits both the painting and stained "stamp" that created it. This process creates a reverse evolution, wherein works such as Self Portrait as the Apostle Paul begin with a mechanically reproduced image from art culture, but ends with repetitive, reductive labor. It becomes difficult to see the finished paintings as truly "abstract' once the process and negated image is known.

Jessica Schnebel is involved with a project she calls "Glamour Incomplete." Schnebel maintains a subscription to Glamour magazine and each time a new issue arrives, she begins a 5'10" painting of the cropped cover. She works on the painting for one month, or until the next issue arrives, at which point she abandons the old painting in order to start a new one. She produces twelve Glamour paintings per year, all incomplete. They are unfinished in the traditional sense (surface coverage, paint quality, convincing image, etc.) but convey their content just as effectively. The images themselves are not of complete magazine covers, but truncated versions. Each painting is "new" without relying on the modernist notion of progress. The paintings, such as February 2004 Glamour Incomplete, are presented on shelves, as a reference to magazine display that simultaneously announces the act of painting more dramatically.

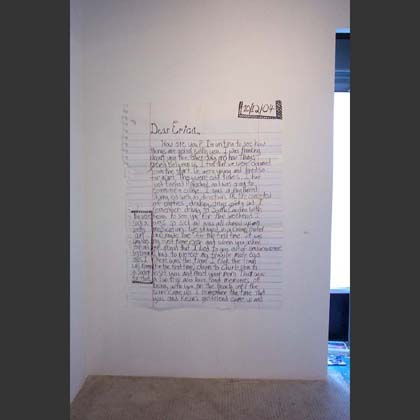

Michael Scoggins also makes large-scale works on paper. In his case, he creates oversize reproductions of notebook paper. The notebook paper becomes the form within which he revisits imagery from childhood, or more exactly, a male childhood. The fantasies, neuroses, and power relations of childhood are enlarged with deadpan coolness in works like Dear Erica and How I Spent My Summer Vacation. He has exhibited what looked like oversized homework assignments, punitive sentence repetitions, and fantastically complex drawings of staged battles. More recently, he has manipulated the oversized notebook paper to form paper airplanes, paper footballs, and crumpled wads. The unexpected scale alone allows viewers a flash of remembrance to a time when the body felt much smaller in relation to the world it occupied.

Eric Standley destabilizes the use value of painting while still spending long hours in the studio. Standley makes small-scale representational paintings on linen using the traditional techniques of underpainting and glazing. When the paint has dried, Standley carefully cuts the linen into a shoe pattern. He then sews a pair of shoes for himself from what had previously been a painting. For the next step he builds lined wooden boxes for the shoes that are displayed on shelves. The exterior lid of each box has a small photographic image of the original painting. Standley's work, such as Dinosaur or Ruby, starts within the most private and historically stable definition of painting, but is then shoved onstage into the world of commodity and functionality. By the end they plateau in a nether world that has aspects of both, but allegiance to neither.

Alexis Terry has begun making elaborate wall installations from cans of pigmented plaster. Terry, who has also done endurance-based performance work, gathers and cleans the cans herself. She then fills each can to the brim with pigmented plaster, extending a screw from the bottom of the can. The original commodity function of the cans vanish as they become cylinders of pure color. For a recent piece she arranged 500 cans on the west wall of a gallery to form the sunset constellation pattern. The earthbound materials came to convincingly represent the distant sky. In 05-07-05 / 7:00 PST Los Angeles, California, Terry has recreated the constellation pattern for the night of the Semiconductors opening reception.

Semiconductor Exhibition Images

(All

images by Craig Drennen.)

Fred Jesser, Fabulous: Part II; Alexis Terry: 05-07-05/7:00 PST, Los Angeles, California; Avantika Bawa, (...); Heath Ritch, (Self-Portrait as the Apostle Paul); Brett Callero, The Eagle Has Landed; Jessica Schnebel, Us Weekly Issue 489

Lauren Clay, Proposed Communal Hideaway Unit for Virgins; Eric Standley, Sectioned; Heath Ritch, Self-Portrait as the Apostle Paul; Alexis Terry: 05-07-05/7:00 PST, Los Angeles, California; right wall from back: Avantika Bawa, Heath Ritch, (Self-Portrait as the Apostle Paul); Brett Callero, The Eagle Has Landed

Eric Standley, Ruby; Eric Standley, Sectioned; Heath Ritch, Self-Portrait as the Apostle Paul; Alexis Terry: 05-07-05/7:00 PST, Los Angeles, California

Heath Ritch, Self-Portrait as the Apostle Paul; Alexis Terry: 05-07-05/7:00 PST, Los Angeles, California, Avantika Bawa, (...)

Heath Ritch, (Self-Portrait as the Apostle Paul); Brett Callero, The Eagle Has Landed; Jessica Schnebel, Us Weekly Issue 489, Jessica Schnebel, February 2004 Glamour Incomplete, Craig Drennen, Helen Slater as Supergirl Front, Craig Drennen, Helen Slater as Supergirl Back, Michael Scoggins, Dear Erica

Michael Scoggins, Dear Erica; Fred Jesser, Fabulous: Part II; Lauren Clay, Kaput; Lauren Clay, Proposed Communal Hideaway Unit for Virgins; Eric Standley, Dinosaur

Avantika Bawa, (...)

Craig Drennen, Helen Slater as Supergirl Front

Craig Drennen, Helen Slater as Supergirl Back

Michael Scoggins, Dear Erica