TILT and deStructures

Jasmina Tumbas

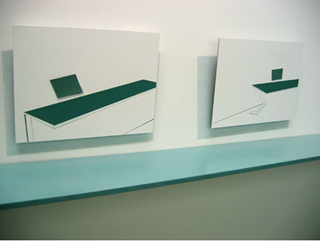

TILT – Avantika Bawa, 2005

This tension of spatial illusion and human cognition, as well as the challenge to minimalist aesthetics, is an underlining principle within the work of Prema Murthy and Avantika Bawa, currently exhibited at Saltworks Gallery, Atlanta. Both artists explore the realms of human cognition and perceptual discrepancies in a culture that has an increasingly fast pace and is inundated with information overload. While Prema Murthy’s digital art is primarily concerned with immigration pattern as data transformation across various perceptual levels, Avantika Bawa approaches this problem with her architectural consideration and deconstruction of space.

In TILT (2005), Avantika Bawa plays with our well-trained perception of linear perspective and our natural inclination to confine space in order to understand it as a whole. This theoretical understanding of perception is an underlining principle within Gestalt[1] psychology and a critical idea in Minimalism. In minimal art, primary forms, such as squares, rectangles and circles, are fundamental. Bawa questions this organization of space by using some of the underlining principles of minimalism, but “tilting” them and therefore creating something that is disorganized. In Bawa’s juxtaposition of the “primary” and therefore minimal forms of squares and rectangles with the tilted lines and perceptual illusions, the spatial relations become unmanageable. The viewer cannot relate to her work through reason and is forced to overcome this urge to organize space. This tension in her work confronts the viewer with at least one question: Is it not the uncontrollable, the things that cannot be rationalized and reduced to their primary forms that allow difference and room for discussion?

The site specificity is not only fundamental to the success of the installation TILT, but is also an important aspect to how Bawa works.[2] Her architectural approach to creating spatial tension is related to the particular spaces of her choice and is therefore site specific. The architectural space, the colors and the design of the gallery itself become contributing factors to the piece. Saltworks Gallery, a former piano warehouse, provides the viewer with a sense of uneasiness not only upon entering the space, but already in its exterior architecture. The building is barely identifiable as a gallery. When we enter the gallery, we pass through the first exhibition hall, in this case Prema Murthy’s work, to enter a hallway that seems to lead to another space. However, this hallway becomes the site for TILT. The installation itself demands the viewer walk through; it demands a decision to engage in the artwork, which contests the supremacy of self-referentiality within minimalist aesthetics.[3] The lines between art object and the rest of the architectural space become blurred and we find ourselves asking questions such as: Is this part of the exhibition? What belongs to this piece? Where does it end? The struggle of finding an answer is where Bawa’s power lies. She does not give us one. Like the rest of her work, she forces us to think– preferring to instead open up a room for discussion.

Bawa’s deconstruction of the traditional use of trompe-l’oeil[4] in still-life painting creates visual and conceptual tensions within the work. The illusion of space and color is essential. The two walls that only seem to converge at a vanishing point but which are in fact parallel suggest a reference to the Gestalt principle of the phi phenomenon.[5] Although there is no clear vanishing point, the viewer draws an imaginary line in an attempt to form a unified whole. It is the reference to something that is absent which makes it present. The same principle applies to her use of “fake” shadows. The drop shadows behind the Plexiglas framed collages are deceiving; they are painted and hence not “real” but they mimic reality. Collages intrinsically push limits of two dimensionality and spatial illusion. The monochromatic use of color, a neutral green and the sterile white, intensify the confusion of shadow and color and induce a sense of plasticity. This sense of plasticity is enhanced by the beaming neon light above the hallway that exemplifies the lighting within modern spaces, such Doctor’s offices, police stations, schools, airports, malls and, as demonstrated here, museums and galleries.

Demographia, (video projection) – Prema Murthy, 2005

The trend within museums to label and confine the artwork is also challenged by Bawa. She creates an effective sense of instability and uncertainty in her use of spatial illusion. The tilted shelves confront the intellectualized understanding of space and induce a sense of insecurity. The shelf is no longer a stable and functional base for books, and only references something that is not there but which is placed within our conceptual understanding of space. She therefore successfully turns the debate towards the audience and forces us to think outside the box. She alludes to the monumentality of art and plays on the limitation of confinement within a museum or gallery setting.

This sense of unsteadiness is accentuated evermore by the suggestion of a base that usually functions as a support for the shelf. In this case, the base appears to be useless. However, from a distance, the base for the shelf can be seen as a base for the wall, in which case the walls threaten to collapse and fall on one another. This lurking tension is underlined further by the aesthetic separation of the two walls through the use of two diagonals, inbuilt within the architectural space of the gallery. The diagonal within the concrete ground creates a mirror line between the two walls, by which the asymmetrical space can be organized in a symmetric whole. However, the symmetry is not absolute. Bawa breaks our inclination to finally have found the answer to the confusing juxtapositions by tilting the symmetry and leaving us once again, with no definite answers. While she seems to embrace Wölfflin’s principle of absolute clarity, formally, she refutes it at the same time and pushes the limits of the radical formalism of minimalist aesthetics.

Murthy takes a different but equally intriguing approach. In deStructures (2005), she challenges modernity in its rationality, creating a vision of movement through the use of statistical data. She synthesizes numerical data, animation, computer technology and the human figure into an interplay of organic shapes that move in snapping motions and continuously collapse into one another to shape new forms. The rationality and logic of a world that can be calculated and measured are rendered volatile, becoming instead mobile and unpredictable forms. In this way, Numerical value is suspended within the artwork. At the same time, Murthy also challenges minimalist aesthetics. The primary forms of minimalism are the fundamental structure on the surface, such as the angular shapes of squares, triangles and rectangles, but they are out of control. Here, like with TILT, we find a reference to something that is or should be in order but which is actually not. With this tension, Murthy successfully challenges minimalist aesthetics and the emphasis on the organized, the coherent within modernity.[6]

Murthy also raises an interesting and very important question in regard to the limits of numerical representation of people. What do numbers reflect about a society? Murthy plays with this discrepancy of numerical reduction of by employing the numbers as a structural fundament for the different shapes. While Bawa relates to the migration issues in her deconstruction of formalism, Murthy takes an even stronger social and political edge. This is a central point of inquiry for her, as well as artists like Salgado,[7] who have struggled and still struggle with the discrepancy of finding “the right way” to reflect sociological conditions. The inability to comprehend the reality of people’s situation is related to the information-overkill and desensitization of perception within modernity. Murthy forces us to face the consequences of our inclination to reduce people to numbers, their skin color and to anonymous figures that we are then unable to relate to.

deStructures (installation view, Saltworks Gallery) – Prema Murthy, 2005

The use of color, although in both works political, is a lot more conceptually significant for Murthy’s piece. The colors used for the angular shapes that define the space are related to what are perceived as stereotypical skin colors. These colors form the basis for the forms, but do not divide space; they are part of the whole and there is no comfort in separating the shapes from one another. Instead, Murthy forces us to look at them as a whole as a Gestalt, autonomous and at the same time dependent on the structure of the whole. She refutes the legacy of functionalism, structuralism and utilitarianism by using some of the aesthetic procedural characteristics, such as mathematics and computer-based numerical analysis, whilst contesting them at the same time with her organic, uncontrollable figural experimentation.[8] These tensions leave room for conversation and conflict which is a democratic approach to art. Like Bawa, Murthy negates the persuasiveness of a definite answer and invites the viewer to form their own opinion.

The most intriguing aspects of both TILT and deStructures are embedded in their underlining narratives. In essence, a narrative defies minimalist self-referentiality but includes the human and political aspect, essential to both exhibitions. Prema Murthy as well as Avantika Bawa embrace the narrative of migration and nomadicism as their conceptual basis. Both artists examine the political realm within art. TILT, the work of a practicing artist and professor in the U.S. and a native of India, communicates a narrative of tension, struggle and isolation through the formal tensions within the work. Murthy places this struggle into a narrative that concerns the city of Atlanta. She refuses the temptation to show identities in her work and leaves the viewer with the suggestion of the figurative, a falling hand, a face moving bye, and an angular shaped breast.

Now, to answering the very first question I posed at the beginning: Is it not the uncontrollable, the things that cannot be rationalized and reduced to their primary forms that allow difference and room for discussion? Both Bawa’s and Murthy’s exhibitions lead me to answer this question with an urge for discussion and search for different ideas. It is an interesting exhibition that poses questions with no definite answers, while addressing pressing socio-political issues that are fundamental to American culture today.

TILT (detail) – Avantika Bawa, 2005

Bibliography

Schultz, Duane P. and Sydney A. A History of Modern Psychology. (Orlando: Harcourt Brace and Company, 2000).

Endnotes

[1] The Gestalt movement in psychology is primarily concerned with the perception of objects as whole, not merely a summation of the parts. In the early 20th century, Max Wertheimer, Wolfgang Kohler, and Kurt Koffka initiated the anti-functionalist and anti-behaviorist movement that was focused on perception and which preceded later cognitive psychology (A History of Modern Psychology, Duane P. Schultz and Sydney Ellen Schultz).

[2] In an interview on October 7, 2005, she expressed the importance of site specificity of her work.

[3] Minimalism is inherently self-referential because it is not supposed to allude to anything else but itself. “Art for art’s own sake,” as Clement Greenberg stressed, becomes the focus.

[4] Trompe-l’oeil is a French term and can be translated as fooling or deceiving the eye.

[5] Max Wertheimer discovered this particular phenomenon in the early 20th century. Two or more stationary lights, if lit in temporal proximity, would appear as moving and would create a whole new “Gestalt.” That new Gestalt could not be simply reduced to its parts, as Wundtian psychologists would suggest, because two stationary lights are never moving (A History of Modern Psychology, Duane P. Schultz and Sydney Ellen Schultz).

[6] Modernity in this context is used as a descriptive term for the increasing fast pace and technological culture, as well as the strong appeal to reason and science as a major point of reference.

[7] Salgado’s photo-documentary work has resulted from his struggle with numerical data and its inability to communicate the “reality” of the human condition.

[8] With the legacy of functionalism I refer to the Wundtian perspective in psychology that understands human perception in its separation into individual bits, unlike Gestalt, that looks at the whole.

Jasmina Tumbas is an international student and a M.A. candidate in the Savannah College of Art and Design's Art History program. She is currently working on her thesis concerning the politically charged performances and conceptual works of contemporary artist Santiago Sierra. Questions or comments can be emailed to jtumba20@student.scad.edu.

©2006 Drain magazine, www.drainmag.com, all rights reserved